In the village of Tarup, four kilometres northwest of Odense in Denmark is the Island of Fyn where, during World War 2, the German Gestapo [Geheime Staatpolizei-State Police] had

requestioned the 'Husmandsskolen' a former agricultural school as one of their area headquarters. It was one of a few such establishments throughout Denmark to keep the Danish people under

subjugation and eliminate any resistance to German occupation. The Gestapo had taken over all investigations concerning the resistance movement. At the beginning of 1944, the Germans began

a campaign of 'counter terror.' Counter sabotage and reprisal murders were carried out in retaliation for sabotage actions and attacks against the Wehrmacht [German army] and German

attempts to persuade the Danish police to take part in prevention of sabotage and maintaining law and order failed. The police force was disbanded on 19 September 1944 and its members were

subsequently sent to concentration camps.

Known to the locals as 'Torture Castle' the Husmandsskolen was, in early April 1945, surrounded by barbed wire fences and strict surveillance was enforced. Having been taught a painful but

valuable lesson by Royal Air Force bombing raids on other Gestapo buildings in Denmark, the Husmandsskolen had been thoroughly disguised from enemy aircraft by camouflage netting. The

Germans were determined not to be caught by the 'Gestapo Hunters' with their pants down again.

This undated, pre-war image shows the Husmandsskolen in its prime, an attractive agricultural school. Under the Gestapo’s occupation locals christened this peaceful building the 'Torture Castle' as its rooms filled with prisoners. (via Ken Wright)

The deHavilland Mosquitoes from 140 Wing 464 Squadron had earned their enviable reputation by their low level precision pinpoint bombing of the Gestapo prison in Amiens [France] on 18

February 1944 and the Danish Gestapo headquarters in Aarhus 31 October and Shell house in Copenhagen on 21 March 1945. Buoyed by the successful destruction of these Gestapo buildings, the

Danish resistance reasoned that if the Husmandsskolen could be destroyed, the Gestapo would be effectively put out of business in Denmark. The resistance leaders again asked RAF 140 Wing of

the 2rd Tactical Air Force for help to drive the final nail into the Gestapo's coffin. This Wing under command of Air Vice Marshal Basil Embry consisted of 464 Squadron, Royal Australian

Air Force, 487 Squadron, Royal New Zealand Air Force and 21 Squadron, Royal Air Force. It was not without some justifiable pride, that the three Squadrons were again tasked for the job.

From the Squadron airfield at Melsbroek in Belgium, 6 assorted Squadron Mosquitoes from 140 Wing took off at 2pm on the afternoon of 17 April carrying both fuselage and wing 500 lb bombs

with delay fuses of 11 to 30 seconds. On this operation, wing fuel tanks were not required due to the short distance to the target area. The six Mosquitoes were led by Group Captain Bob

Bateson and the Wing Tactical Navigation leader, Squadron Leader Ted Sismore, who had successfully planned and participated in the Shell house raid and had used his considerable talent to

plan this particular raid. Amongst the aircrew was Air Vice Marshall Basil Embry, using the pseudonym 'Wing Commander Smith', as he had done previously when, against orders, he flew on two

previous raids against the Gestapo in Denmark.

RAF high command didn't like the possibility of losing their top ranking officers who they thought were more useful to the war effort if they did their flying from behind a desk. Embry, if

the opportunity arose, was out flying missions. 'I personally thought it only prudent to hide my identity as the Germans had circulated a description of me and put a substantial price on

my head after my escape from France in 1940 so I became Wing Commander Smith with the number of a genuine Smith of that rank whenever I flew on operations. I had identification discs made

and marked all the clothes in which I flew with his name.'

Air Vice Marshall Basil Embry. (via Ken Wright)

There may have been more to Embry's statement than meets the eye. As one ex member of 464 Squadron recently commented; 'As Embry was one of the privileged few who knew about the Enigma

codes and Benchley Park's work, he had to get the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill's permission to fly. Churchill reluctantly gave his permission providing he always took with him

his cyanide pill.' Unknown to the men who were to about to participate in the attack, this was to be 140 Wings' last pin point raid in Denmark as the war would end 21 days later.

Eight Mustang Mk.IIIs from RAF 129 Squadron flew as escort against enemy fighters and deal with the flak positions known to be located around the target area. The formation quickly

assembled over Brussels and headed north. Crossing low over the Netherlands, they continued to the Helgoland Bugt, crossed the Jutland Peninsula and onwards to Fyn. Embry was later to

remark; 'On the Aarhus raid I had rarely flown behind a better leader than Bob Bateson who had with him a very able navigator, Sismore, to help steer a perfect course to the target.'

At 4:05 pm, the air raid sirens in Odense began to sound alerting everyone that enemy bombers were heading towards the city. Although the navigation was spot on, the target was very

difficult to find because of the effectiveness of the camouflage. As a result, the attackers had to circle the area for almost 30 minutes before the target was finally identified and three

bombing runs had to be made with the 11 to 20 second delay fused bombs being dropped on the fourth. The fifth run was made by the FPU [Film Production Unit] cinefilming aircraft piloted by

Lieutenant Ken Greenwood. Spending so long over the target area should have invited the attention of Luftwaffe fighters but the raiders were lucky as no enemy aircraft appeared.

Obscured by a plume of smoke and dust the camera records an image of a bomb landing on the Husmandsskolen. (via Ken Wright)

The only Mosquito to be damaged during the attack was flown by Flight Lieutenant William McClelland and Sergeant Jack Barr as navigator. A bomb blast had knocked out an engine but was still

able to be flown on the remaining engine. The crew managed to fly on and made a precautionary landing at Eindhoven airfield in the south of the Netherlands which was in Allied hands. The

remainder returned to Melsbroek without incident. Two days later a Spitfire from 16 Photograph Reconnaissance RAF Squadron after overflying the target area submitted a report. Two thirds

of the main buildings had been completely demolished and the remainder gutted. What were once living quarters had also been destroyed and some of the outlying buildings were severely

damaged. Later intelligence reports established that possibly 12 of the 28 bombs dropped were responsible for 20 civilian houses destroyed and another 150 damaged. In addition to the loss

of property, nine Danes were killed and 20 were injured. It was concluded that although the bombing was accurate, the collateral damage to buildings and loss of life near the target was due

to the weight of the bombs. Some had simply bounced off the rubble into the suburbs beyond. The escorting Mustang fighter pilots must have been quite happy or disappointed, depending on

the individuals' perspective, as they only one anti-aircraft position near the target area had to deal with.

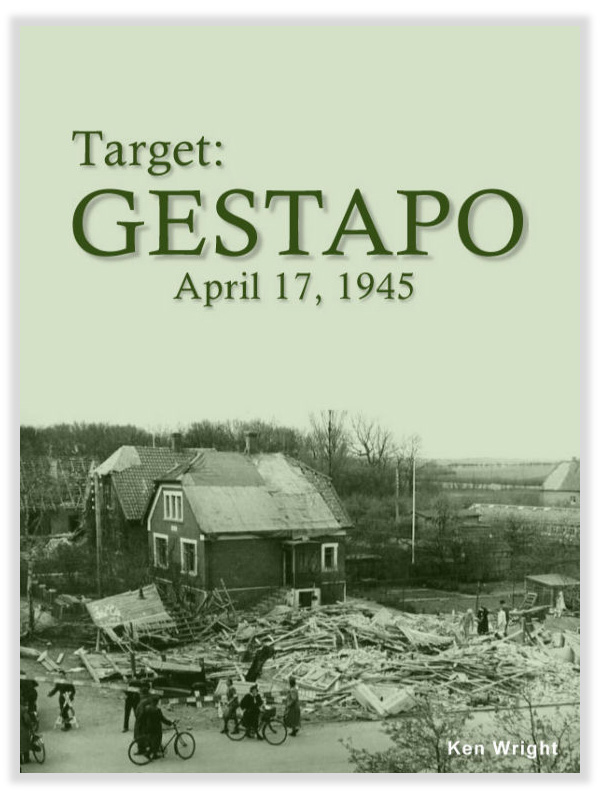

Reconnaissance photos later showed that the Mosquitoes of 464 Sqd (RAAF), 487 Sqd (RNZAF) and 21 Sqd (RAF) succeeded in destroying the once beautiful Husmandsskolen. Two-thirds of the building was levelled while the remainder was gutted and unusable. (via Ken Wright)

Despite the best intensions of the planners and pilots, civilians were still killed and injured during the attack. Bomb blasts and errant bombs destroyed 20 houses and damaged another 150. Here, bicycle riding locals gather around a collapsed house while officials begin erecting a barricade. (via Ken Wright)

A line of automobiles parked along the street show damage from the bomb blast. It's easy to understand how the civilian houses collapsed when facing the same explosive force. (via Ken Wright)

Because of the Copenhagen raid in March, the Gestapo had made it standard practise for prisoners and staff to practise air raid drills every day with the result that when the RAF came

knocking that fateful afternoon, no one was home. No prisoners were killed although one Gestapo official died. While the RAF Mosquitoes were making several circuits attempting to find the

target, it would have been a warning to the civilians nearby as well of an impending attack and had they not taken cover or dispersed, the loss of life may have been much greater.

The Gestapo did not have long to find an alternative building to hold their prisoners as German forces in Denmark surrendered to the British on 5 May and on the morning 7 May 1945, the

Germans signed an unconditional surrender document officially ceasing military operations in Europe the next day. After the end of hostilities, the Squadrons aircraft were employed on

escort missions over the newly liberated Europe for VIP's, including the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Crown Prince Olaf of Norway and General Alfred Jodl who signed the

surrender agreement for Germany.

In post-war Denmark in early September, a ceremony was held in the biggest store in Aarhus during which Air Chief Marshal, Sir William Sholto Douglas, Air Commander-in-Chief, British Air

Forces of Occupation, presented a cheque for 470,000 kroner, about 20,000 pounds at the time, to the Crown Prince of Denmark. This monetary gift was to aid the Danes injured during the

Aarhus, Copenhagen and Odense raids. The money had been collected from the proceeds of two big RAF fly-past which took place in June and July of which half the population of Copenhagen were

spectators. Among those present at the presentation ceremony were the surviving crews who took part in the three 'pinpoint' raids in Denmark.

Air Vice Marshall Embry (aka: Wing Commander Smith), DSO DFC AFC RD is seen with Squadron Leader Peter Clapham, DFC RD. (via Ken Wright)

With their services no longer needed, Squadrons 464 and 487 were disbanded in Belgium in September 1945 whilst 21 Squadron continued duties as part of the occupational forces in Germany for

a further two years. They were finally disbanded in November 1947.

During the war, the young men of the Squadrons had a 'do or die' feeling that only those who flew would understand not least due to the fact that their participating top leader [Embry]

always ran the same risks as the youngest pilot. The esprit-de corps and the camaraderie that they had established has been kept alive through associations, memorial services and personal

contact but time has taken a toll on those brave young men in their flying machines. Those that have gone and those who remain gave history an amazing legacy.

Footnotes:

1 - Reference to the book; The Gestapo Hunters. 464 Squadron, RAAF, 1942-45. M. Lax and L. Kane Maguire. Banner Books. Australia.1999.

A special thanks to Danish author Ove Hermansen for his invaluable advice and corrections.

2 - Flight Lieutenant Peter Lake-conversation with author, November 2010.

3 - There were two reports and the figures of buildings destroyed or damaged both varying slightly.

4 - Page 228. The Gestapo Hunters.